The Road to 270: Illinois

By Seth Moskowitz

April 20, 2020

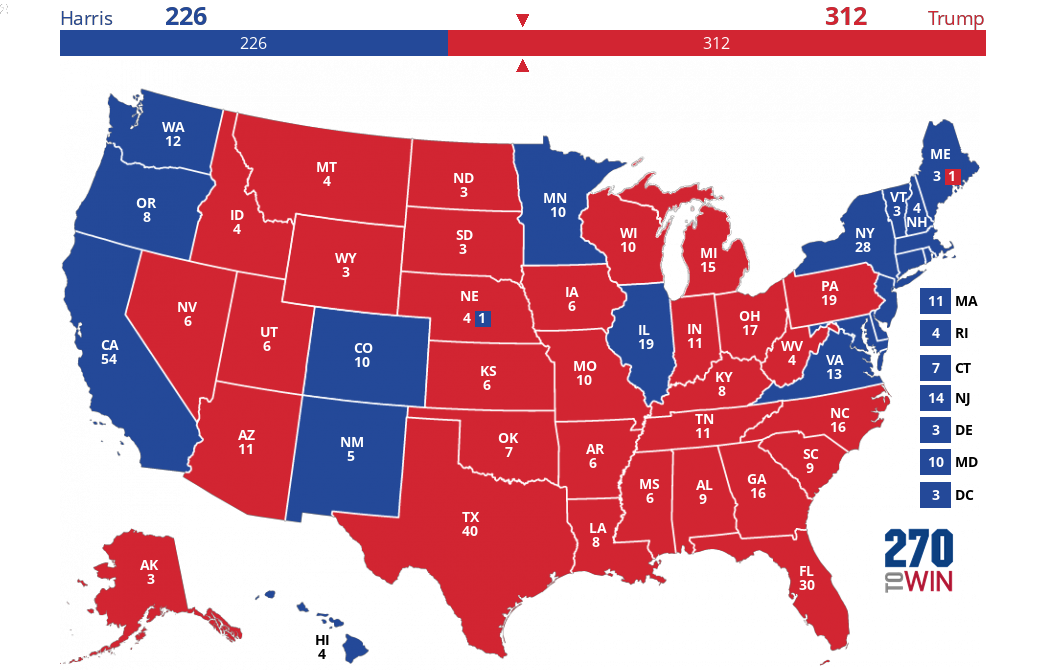

The Road to 270 is a weekly column leading up to the presidential election. Each installment is dedicated to understanding one state’s political landscape and how that might influence which party will win its electoral votes in 2020. We’ll do these roughly in order of expected competitiveness, moving toward the most intensely contested battlegrounds as election day nears.

The Road to 270 will be published every Monday. The column is written by Seth Moskowitz, a 270toWin elections and politics contributor. Contact Seth at s.k.moskowitz@gmail.com or on Twitter @skmoskowitz.

Illinois

Illinois was once America’s political bellwether. From 1896 to 1996 the state regularly swung between the parties and voted for the winning presidential candidate in every election except for two. But since 1992, it has voted Democratic in every presidential election. Why is the state that is most demographically similar to the nation overall no longer a swing state? In short, Democrats traded voters in shrinking rural Illinois for voters in Chicago and the suburbs. The longer story starts before Illinois was a state.

Statehood, Growth, and Abraham Lincoln

The territory we now know as Illinois was first discovered by French explorers in 1673 and settled about 50 years later, in 1720. It was passed into British hands in 1763 when France lost the French and Indian War. Finally in 1778, amid the Revolutionary War, the United States took over the region. Current-day Illinois was first claimed as a part of Virginia, then as a part of the Northwest Territory until 1809, when the Territory of Illinois was created.

Through all this, the Illinois Territory wasn’t attracting many settlers. Inhabited mostly by Native Americans, European fur trappers, and some migrants from the southern United States, it had a population of just 60,000. Even with this abnormally small populace, Congress agreed to admit Illinois as the 21st state in 1818, expanding the territory to include the ports of Chicago as it did so.

Chicago was founded in 1833, an act that would change the character of the state. On the southwest corner of Lake Michigan, Chicago was destined to become a transport hub, connecting the northeast and midwest through the Erie Canal, Lake Huron, Lake Michigan, and the Mississippi River basin. Canals and railroads came quickly and by the mid 1850s Chicago dominated Illinois commerce.

Even though 3,000 Mormons left the Illinois town of Nauvoo after leader Joseph Smith Jr. was murdered, Illinois grew at a rapid clip. In 1848, the same year of the Mormon exodus, the population had reached nearly a million and the state was celebrating the opening of the Illinois and Michigan Canals.

By that time, the state’s most celebrated politician, Abraham Lincoln, had already been seated as a U.S. Representative. Over the next ten years, Lincoln’s political presence would only grow as he proposed abolishing slavery in Washington, DC, ran and lost an election for U.S. Senate, was considered for the Republican Vice Presidential nomination, and fought against the Kansas-Nebraska Act and Dred Scott Supreme Court Decision. In 1858, Lincoln again makes a run for the Senate against incumbent Stephen Douglas, the two of whom battled it out in the historic Lincoln-Douglas debates. Again, Lincoln loses. The loss launches Lincoln into the national spotlight as a leading voice against slavery and three years later, in 1861, he is inaugurated as the president of the United States.

Lincoln’s home state, though, wasn’t entirely supportive of his presidency nor the Union cause in the Civil War. In the 1860 election, Lincoln only beat Douglas, a fellow Illinoisan, 51% to 47%. Much of southern Illinois supported the Confederacy even as 250,000 Illinois soldiers fought in the Union Army. During and after the war, the rebellious southern parts of the state would be overrun by anti-slavery, pro-union, Republican dominated northern communities.

Growth and Wars

During the Civil War, Illinois had been a primary supplier of grain, meat, and weapons to the Union army. These industries only continued to grow after the war and needed workers. In 1871, a fire killed 300, left 100,000 homeless, and destroyed over 15,000 buildings in Chicago. The city bounced back to become the preeminent midwestern city for commerce and culture. Transplants — including many newly freed slaves — came to Illinois and Chicago to work in the stockyards, on the railroads, in manufacturing, in mines, and to produce grain. Just nine years after the Chicago fire, Illinois was the fourth most populous state. Chicago would continue to grow and diversify as western Europeans, Jews, Poles, Italians, Czechs, and black southerners all continued to build communities in Illinois.

The two World Wars, the Great Depression, and their aftermath brought change to Illinois. In both wars, thousands of Illinois men were sent to fight in Europe. The state’s manufacturing, mining, and farming industries pumped out goods to provide for the war efforts. While growth stagnated during the 1930s and the Great Depression Era, the economic growth spurred by both wars led to population increases of around one million in each decade of the 1920s, 1940s, and 1950s.

As with most of the nation, Illinois supported Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and voted Democratic from 1932 to 1948. As the Chicago suburbs grew following World War II and became Republican strongholds, Illinois became a swing state. This suburban growth was offset by minority populations — blacks from the south, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans — and the tight grip of Democratic machine politics in Chicago.

Notorious for corruption and patronage, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley consolidated Democratic support among the city’s urbanites. The machine united union workers, minorities, immigrants, and Jews to help Democrats dominate Chicago and keep the party competitive in state and federal elections. Daley served from 1955 through 1976, by which time Chicago was facing deindustrialization and closing factories and stockyards. The city’s population shrunk from 3.6 million in 1970 to 2.8 million in 1990 as jobs left the city, unemployment grew and crime rose.

During all this change, Illinois swung between the parties. It voted for the moderate Republican, Dwight Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956 over native Illinoisan Adlai Stevenson, Democrats John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson in 1960 and 1964, and Republican candidates from 1968 through 1988.

Along with this latter string of Republican presidential successes, Republicans would also dominant the Illinois governorship. Beginning in 1977 through 2003, Republican governors would lead the state. These Republicans, according to today’s standards for the party, were progressive. They advocated a more robust social safety net, increases in public pensions, pay-as-you-go pension funding, and infrastructure spending. This poor fiscal stewardship, along with continued corruption and struggles by successive governors, led to the fiscal crisis and near-“junk” credit rating Illinois now faces.

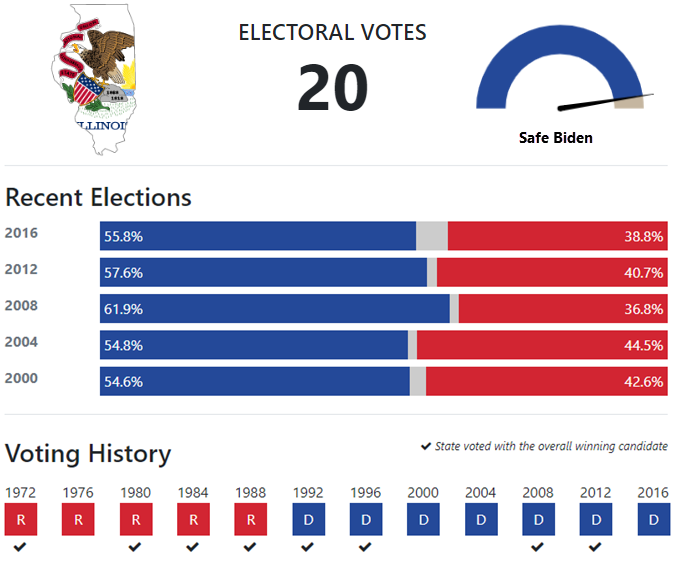

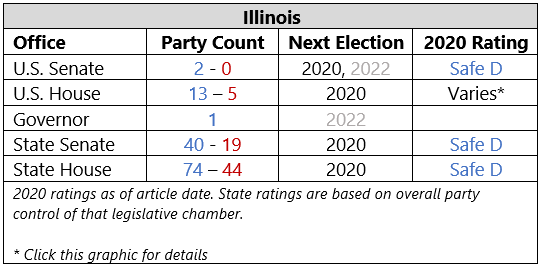

Even through these struggles, Chicago remains one of the nation's largest cities, propped up by financial, business, technology, and education sectors. The city’s successful transition to these new-era industries helped stanch the population bleeding of the 1970s and 1980s. Still, Illinois continues to grow more slowly than the rest of the country. This has significantly reduced the state's clout on the electoral map. In the 1920s and 1930s Illinois had 29 Electoral College votes. By 2012 that number was 20 and is likely to drop to 19 following the 2020 Census.

A Bit of Geography

Before looking at the state’s recent electoral history, a bit of geography will be useful. I divide the state into seven pieces.

1) Cook County and Chicago. Chicago is the third largest city in the United States and more diverse than the nation as a whole, with just 33% of residents identifying as non-Hispanic white.

2) Chicago’s suburban collar counties. These counties are highly educated and whiter than Cook County and Chicago.

3) Chicago’s exurban counties. As you move further outside of Chicago, the communities get less educated, less wealthy, and more white. The state’s rural character blends with commuter suburbs and industrial towns of the Fox River Valley.

4) Sangamon County and Springfield. Located in the center of the state, Springfield is the state capital and biggest city outside of the Chicago area.

5) St. Louis Metro. Just across the Mississippi river from St. Louis, Missouri, is East St. Louis and the St. Louis suburbs.

6) Rural Northern and Central Illinois. This region is dominated by agriculture and manufacturing, far less dense and much whiter than the state overall. With Chicago nearby, this region also has industrial towns and some small cities.

7) Rural Southern Illinois. This region relies on agriculture and farming like up north but has more coal and petroleum extraction. Culturally, it has a evangelical conservatism reminiscent of the southern United States. This region is whiter and more religious than the state overall.

Recent Elections

Starting in 1992, Illinois, once a bellwether, would be reliably Democratic. Bill Clinton’s 1992 and 1996 victories were powered by the traditional Democratic voters in Chicago and southern Illinois and new Democratic voters in the state’s rural regions. Many of these agrarian and manufacturing counties had not voted Democratic since Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 landslide. Meanwhile, Republicans continued to sweep the Chicago suburbs.

In 2000, Clinton’s gains in the rural regions began to evaporate. That year, Al Gore still won Illinois, but lost many of the rural counties and votes that Clinton had carried. The outspoken liberalism and environmentalism of the emerging Democratic party didn’t play well in the state’s conservative south. Four years later, in 2004, we see the trend that would dominate Illinois through the 2016 election: urban and suburban counties shifting Democratic and rural ones becoming more Republican. Comparing one urban, one suburban, and one rural county’s 2000 to 2016 results clarify the point. In 2000, Democrat Al Gore carried Cook County (Chicago) by a 40% margin and Franklin, a rural southern county by 9%. Meanwhile, Republican George W. Bush won the biggest suburban county, DuPage, by 13%. Fast forward 16 years and Clinton expanded the margin in Cook County to 53% and flipped DuPage county, winning it by 14%. Meanwhile, Trump carried downstate Franklin County by 45%.

Democrats exchanged shrinking rural regions of the state in favor of growing urban and suburban ones. This trade has kept the state in Democratic hands from Bill Clinton’s victories in the 1990s through Hillary Clinton’s in 2016. It has also balanced Illinois voters, keeping the state remarkably consistent in overall margin from 1992 to 2016. Outside of Barack Obama’s particularly strong showing in 2008, Illinois has voted for Democrats by 10% to 18% in the past seven elections. Over the past two decades, the state’s voters may have reshuffled, but its overall lean has only tilted a few points in Democrats favor.

Given that the state’s urban and suburban regions are growing while its rural ones shrink, Illinois will not become a battleground anytime soon. Illinois is likely to vote Democratic by an even larger margin than it did in 2016, perhaps pushing 20%. While it may once have been a bellwether, Illinois is safely Democratic this November.

Next Week: Connecticut