The Road to 270: New York

By Seth Moskowitz

January 6, 2020

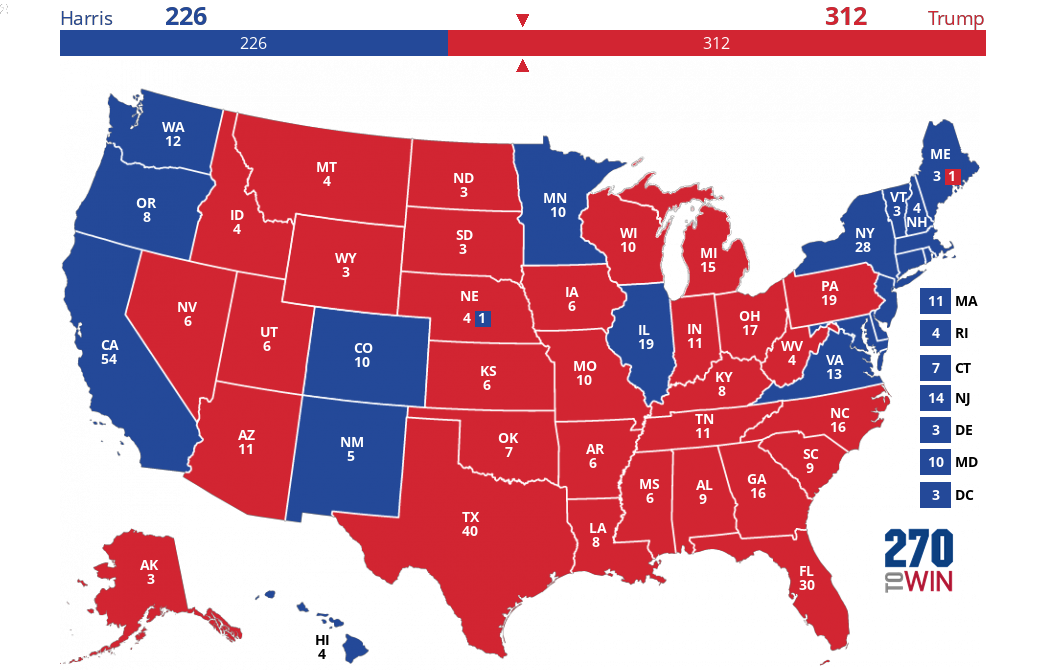

The Road to 270 is a weekly column leading up to the presidential election. Each installment is dedicated to understanding one state’s political landscape and how that might influence which party will win its electoral votes in 2020. We’ll do these roughly in order of expected competitiveness, moving toward the most intensely contested battlegrounds as election day nears.

The Road to 270 will be published every Monday. The column is written by Seth Moskowitz, a 270toWin elections and politics contributor. Contact Seth at s.k.moskowitz@gmail.com or on Twitter @skmoskowitz.

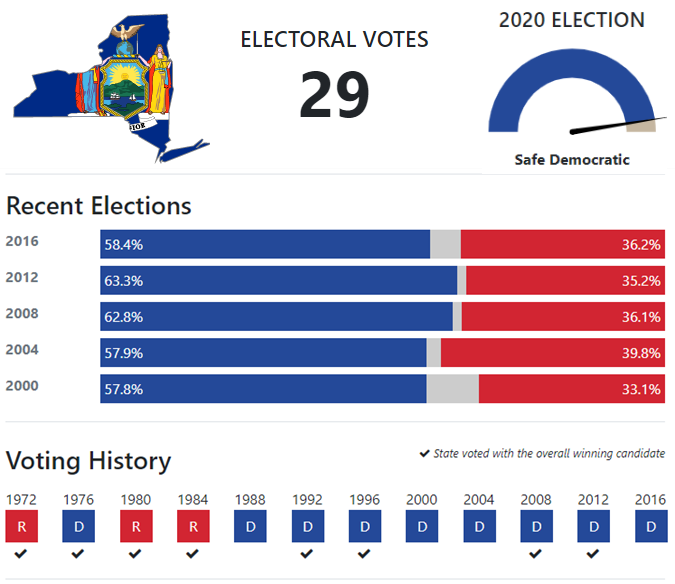

New York

Last Monday, the Census Bureau released its national population estimates. This is the best resource we have for predicting congressional reapportionment that will take place following the 2020 Census. According to these projections, New York will lose one congressional seat, dropping from 27 to 26. Because Electoral College votes are apportioned to states according to the size of their congressional delegation (senators + representatives), New York will likely have 28 electoral votes in the 2024 and 2028 presidential contests instead of the 29 it has today.

This is not a new trend. At its peak in the 1930s and 1940s, New York had 47 electoral votes. It has lost at least two after every Census from 1950 through 2010. We can look at New York’s history and political legacy to understand why it’s expected to, once again, lose representation in Congress and the Electoral College.

Pre-Revolutionary New York

New York City stands on land that was discovered by Europeans in 1524 when Giovanni da Verrazzano first explored the eastern coast of North America. While a fur trade between Native Americans and Europeans began, it took 100 years for the first large group of Europeans to arrive in the region. The settlement was called New Amsterdam and was a part the Dutch colony, New Netherland.

Like New York City today, New Amsterdam was diverse. It was home to Europeans of various nationalities, Christians, Jews, Muslims, enslaved Africans, free Africans, and Native Americans. It was small, though, making it vulnerable to aggression. In 1664, when the English claimed control over the city, the Dutch colonial governor Peter Stuyvesant was forced to surrender. King Charles II gave the new colony to his brother, the Duke of York.

New York was strategically located for the English. It connected the northern and southern colonies, acted as a gateway to the continent’s interior through the Hudson River, and became a popular trading port. However, it was not the most populous of the 13 original colonies. By U.S. independence in 1776, it was the 5th largest.

Regardless of its size, New York played a fundamental role in the American Revolution and America’s early years. It was a home to anti-British sentiment and organizations like The Stamp Act Congress and The Sons of Liberty. The state’s constitution was eventually used as a framework for the U.S. Constitution. And New York City was the nation’s first capital and where The Bill of Rights was written.

After the Revolution

New York’s importance to the new nation would continue to grow for the next 150 years. Home to the New York Stock Exchange, New York City was fated to become America’s financial capital. The state’s convenient location for trade, population of hard-working immigrants, and entrepreneurial spirit also made it a natural home for manufacturing.

Job growth and immigration made New York’s expansion unstoppable in the late 19th and early 20th century. Starting during the Great Irish Famine in the 1840s, millions of immigrants began to arrive at the ports in New York. Ellis Island, which opened in 1892 as an immigration station, became a symbol of New York’s international, immigrant-based culture and economy. Many of these new U.S. citizens settled in the city, building upon its diverse, hardscrabble culture.

By World War I, New York was the nation’s economic powerhouse. The city was home to Wall Street, the nation’s biggest banks, and their associated financial industries. Nowhere roared louder during the Roaring Twenties than New York City. Meanwhile, suburban and upstate New York housed innovative and high-tech companies including GE, IBM, Kodak and Xerox.

Great Depression and War

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 and successive Great Depression devastated New York. Reports of Wall Street brokers jumping from skyscrapers (regardless of their veracity) illustrate the atmosphere in New York City following the market crash. At the depths of the depression, about one quarter of the state was unemployed.

World War II was a boon for the state’s economy. As the most populous state and already home to manufacturing industry, New York was a natural center for defense and wartime manufacturing as well. Through this period, and up until the 1970s, immigration into New York continued to flow. Between 1930 and 1970, the state’s population grew by 45%, from 12.6 million to 18.2 million1. Towards the end of the century, though, New York’s status as an ever-growing state would falter.

By the 1970s, poor financial management brought New York City within hours of bankruptcy. This forced job and spending cuts. About 1 million people moved from the city during the decade. Twenty years later, in the 1990s, a recession would hit New York hard and force a restructuring of the economy. The state shifted away from manufacturing towards becoming a cultural capital with more jobs in the knowledge and service industries. While big upstate companies like Xerox and IBM lost influence, Wall Street and the city were again booming by the late 1990s. Demographic change happened alongside this economic shift as older white, blue collar workers left for less expensive regions of the country and younger immigrants and minorities moved into the city.

The New Century

The September 11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center drew New York into another economic slump. Companies that were previously centralized in New York City dispersed their workforce and 200,000 jobs left the city in 2001 and 2002. Six years later, in 2008, the Great Recession would hit. The financial industry, the epicenter for the tanking economy, took another blow.

New York saw an uneven recovery from the recession. While the financial sector and New York City rebounded, Upstate New York’s revival has been weak or nonexistent. New York City added over 700,000 jobs between 2009 and 2017 in the business, health care, hospitality, and finance sectors. Upstate New York’s private job growth rate, however, was less than one third that of the city’s. Of the 1.1 million private sector jobs created in New York between 2010 and 2018, 985,000 (or 88%) of them are were in New York City, Long Island, or the Lower Hudson Valley.

Population changes followed a similar trajectory. While New York City grew by 2.7% between 2010 and 2019, the rest of the state saw a net population loss of about 1%. In fact, New York saw the largest population loss between 2018 and 2019 of any state in the nation. Even New York City’s population growth has plateaued and started to decline. People are leaving New York for sunnier locales like Florida or for less expensive options in the metro area, like New Jersey.

Presidential Politics Through History

With this historical backdrop, we can look at New York’s political and electoral record. The state’s urban and rural split has been key to this electoral history. Because parties have often been divided along regional lines, these dueling constituencies have often kept New York balanced and competitive.

1789 - 1820

These first elections, when competitive, usually split the country into two voting blocks. There was New England, with its business and manufacturing interests, and the south, with its agrarian and farming concerns. The former states generally preferred the Federalist Party, which advocated for a bigger federal government. The latter supported the Democratic-Republican Party, which promoted states’ rights and less federal interference.

New York — geographically positioned between New England and the south and split between an agrarian upstate and commercial city — didn’t fit neatly into either voting bloc. Generally, though, the state’s electors2 cast their votes for the Democratic-Republican Party, the party of the south and a smaller federal government. Between 1796 and 18203, New York cast its electoral votes for the Democratic-Republican party five of seven times. This is partly because of the state’s rural, plain regions aligned with Democratic-Republicans, partly because the Democratic-Republicans were usually dominant during this period, and partly because both parties frequently placed New Yorkers on the ballot as a way to win over the swing state.

Also important to Democratic-Republican victories was Tammany Hall, New York City’s political machine that influenced state politics through the 1930s. It was originally founded in 1789 to oppose the Federalist Party. In later decades, though, it would dominate New York City’s Democratic Party and claim to represent the city’s working class and immigrant populations. Perhaps most significantly, though, Tammany Hall would become famous for corruption, bribery, and patronage.

1824 - 1852

The 1824 election featured four candidates from the Democratic-Republican Party. While Andrew Jackson won the national popular vote, he did not win a majority in the Electoral College. John Quincy Adams ended up winning the contingent election in the House of Representatives, likely due to a “corrupt bargain” in which he promised to nominate Speaker of the House Henry Clay as Secretary of State. New York’s congressional delegation cast their collective vote for the winner, Adams.

Four years later, with Andrew Jackson’s creation of the Democratic Party, national coalitions again shifted. Generally, the Democratic Party advocated for a smaller government while the Whig Party favored a federal government with power centralized in Congress rather than the presidency. Starting in 1828, New York began to cast its electoral votes by popular vote. From this election through 1852, New York was again competitive and bounced between the two parties. The popular vote swung to the Democratic Party five times and the Whig Party twice.

1856 – 1928

By 1856, the question of slavery had come to dominate national politics. On this, New York was on the side of abolitionists. The Republican Party, formed primarily as a vehicle to oppose slavery, took hold of New York for nearly a century. From 1856 to 1928 New York voted for the Republican nominee in nearly every election4. Around the turn of the century, New York politics was dominated by the progressivism of the era. Voters generally supported local and national candidates who advocated for progressive labor laws, unions, and better government services5.

1932 – 1936

By 1932, New York had been hollowed out by the Great Depression which had happened under the watch of Herbert Hoover’s Republican administration. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition, which brought together labor unions, city political machines, minorities, urban intellectuals and farmers, shifted New York to the Democratic Party.

1940 – 1988

The state’s urban and rural split would again make it closely divided and competitive in presidential elections. Of the 13 elections between 1940 and 1988, eight were decided by less than six percent. The state voted for Roosevelt in his reelections of 1940 and 1944, but flipped back to Republicans in 1948, 1952, and 1956. Then, from 1960 until 1988, the state leaned slightly towards Democrats, only going red in the Republican landslides of 1972, 1980, and 1984.

1992 - 2016

Bill Clinton’s election in 1992 was a watershed year for New York. It marked the end of New York’s status as a swing state. In that election, Clinton dominated Republican George H.W. Bush with a 16 percent margin. The Democratic margin has been higher than that in the six subsequent elections. As the minority voting bloc grew, Jews aligned behind the Democratic Party, white Catholics drifted leftward on cultural issues, and as urban and suburban regions became more Democratic, New York turned from a battleground to Democratic territory.

Recent Presidential Election Landscape

The past three presidential elections in New York have been landslides. In 2008, Barack Obama carried the state by 27%. He expanded that lead to 28% in 2012, even as the national environment shifted 2% rightward. Hillary Clinton’s margin in 2016 was smaller than Obama’s, as she won with a 22% margin over Donald Trump.

Both Clinton and Trump, however, received more raw votes in New York than their counterparts in 2012. Trump got over 300,000 more votes than Mitt Romney, mostly from Long Island, Staten Island, and rural upstate counties. Clinton, on the other hand, expanded Obama’s total number of votes by about 70,000. While she earned about 230,000 more votes than Obama in New York City and its Long Island and Westchester County suburbs, she underperformed his total in the rest of the state by about 160,000.

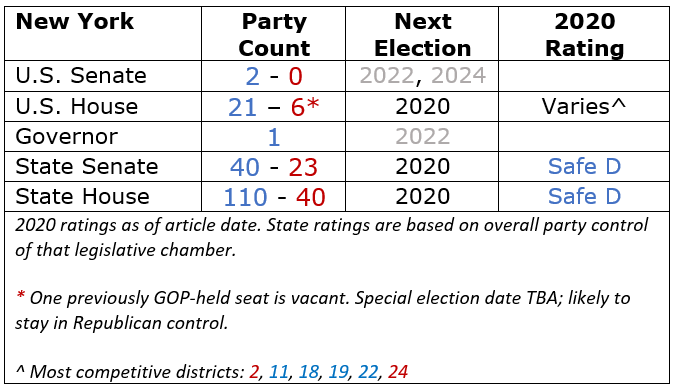

Trump flipped 19 counties that Obama won in 2012, 17 of which were in Upstate New York. The other two — Richmond and Suffolk County — comprise Staten Island and the eastern half of Long Island. The trend in New York mirrors that of the nation: urban areas shifting further to Democrats, rural areas shifting to the GOP, and suburban areas acting as the battlegrounds.

But Trump’s improvement is relative. He still lost the state by 22% and as people continue to leave rural regions in favor of cities and suburbs, New York will likely continue to trend blue. The state may have once been a closely contested presidential battleground, but that status has long passed. As it has for the past eight elections, New York is all but certain to go blue in November.

1 This may seem at odds with the state losing electoral votes beginning in the 1950s. It occurred because the population in other places began to grow even more quickly. As the number of congressional districts is fixed at 435, it is the relative change in each state's population that impacts gain or loss in representation (and thus electoral votes).

2 Through 1824, presidential electors were chosen by the state legislature.

3 New York did not cast electors in the 1789 election due to a deadlocked state legislature. 1792 is not included because George Washington eschewed political parties.

4 There were five exceptions, four of which occurred where the Democratic nominee was a former New York governor (1868, 1876, 1884, 1892). In 1912, former Gov. Theodore Roosevelt ran on a 3rd party ticket, splitting the Republican vote.

5 During this period, both parties pursued relatively progressive policies. The split between them was more regional, a vestige of the Civil War.

Next Week: ![]() Idaho

Idaho