The Road to 270: Louisiana

By Seth Moskowitz

April 13, 2020

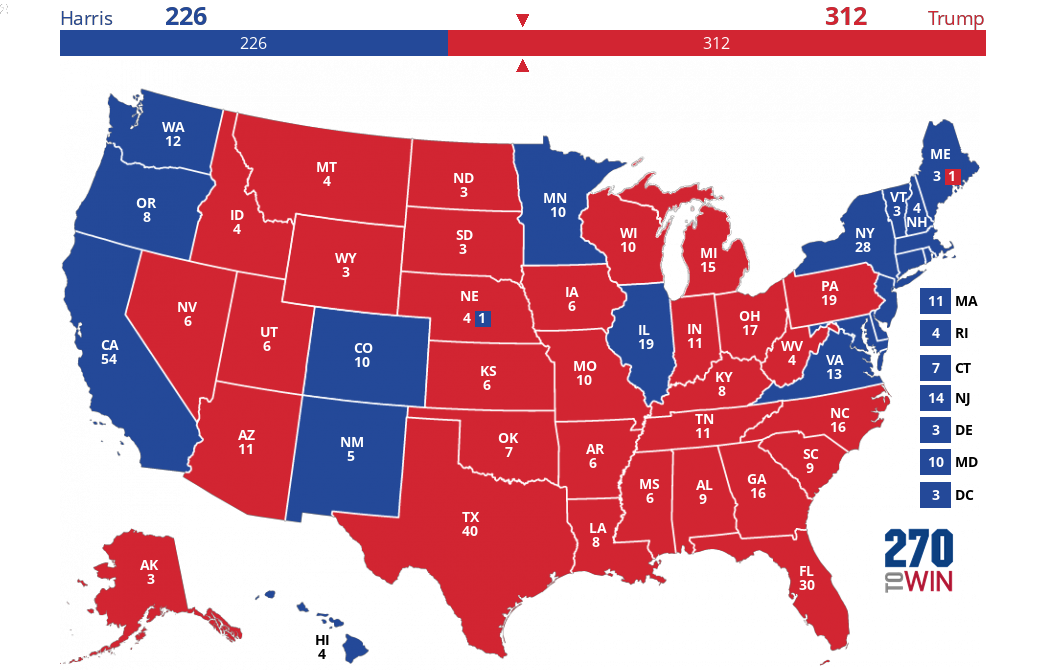

The Road to 270 is a weekly column leading up to the presidential election. Each installment is dedicated to understanding one state’s political landscape and how that might influence which party will win its electoral votes in 2020. We’ll do these roughly in order of expected competitiveness, moving toward the most intensely contested battlegrounds as election day nears.

The Road to 270 will be published every Monday. The column is written by Seth Moskowitz, a 270toWin elections and politics contributor. Contact Seth at s.k.moskowitz@gmail.com or on Twitter @skmoskowitz.

Louisiana

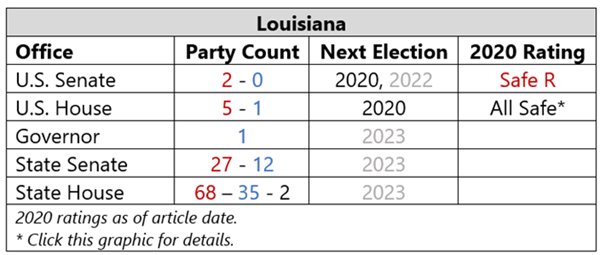

From the Democratic Party’s founding in 1828 through 1944, Louisiana voted for its nominee in all but three of the elections in which it participated. Since 2000, however, the state has been safely Republican and getting more so. The once dominant Protestant-Catholic divide has given way to a Urban-Rural one, a gap seemingly too large for Democratic candidates to overcome. But in 2019, a Democrat did just that by winning the state’s gubernatorial election. This victory does not make Louisiana a realistic Democratic pickup in this November’s presidential election. To understand why, we’ll trace Louisiana’s history from pre-statehood though 2020.

Pre-statehood to Civil War

The first Europeans to set foot in the region we know as Louisiana were Spanish explorers in the 16th Century. The Spanish didn’t settle the territory — that happened about 150 years later in 1699, when France established a colony on the Gulf Coast. France had claimed a huge swath of North America from the Appalachian Mountains to the Rocky Mountains and called it La Louisiane. Not long after, in 1717, the city of New Orleans was founded. France ceded the land to Spain from 1762 to 1800, when the land was passed back to France.

During the brief Spanish rule, the region’s population grew with American settlers, enslaved Africans, and refugees — largely French-Canadians facing British expulsion from Acadia and Haitians fleeing the Haitian Revolution. The refugees, many of them Catholic and therefore welcomed by the Spanish, settled in future-Louisiana’s southwest (now called Acadiana) and New Orleans.

In the eponymous Louisiana Purchase, France sold La Lousiane to the United States. The territory was then carved into two regions — The Territory of Orleans and the District of Louisiana — the former of which was admitted as the 18th state, Louisiana, in 1812.

The new state was a hub for commerce. The Mississippi river was used to transport goods into and out of the United States and New Orleans was the outlet. As Americans moved into the country’s interior, more goods moved through New Orleans. The bustling ports needed workers and immigrants came to fill them. Coming from Germany, Ireland, and Italy, they gave New Orleans a culture more akin to east coast port-cities like Boston and New York than urban areas of the Deep South. During this time, the state’s religious divide — overwhelmingly Protestant in the north and Catholic in the south — ossified.

While the docks of New Orleans stood atop slave labor and the slave trade, the state’s rural regions did so on an even greater scale. The plantation-based economy pitched Louisianans against abolition. Louisiana seceded from the Union and joined the Confederacy in 1861.

New Orleans (with its crucial ports) and the Mississippi River (a way to divide the Confederate South in two) were priorities for the Union. About a year after the Civil War broke out, in April 1862, the North successfully occupied and took over the state.

Reconstruction and Civil Rights

In the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, Louisiana, along with its southern neighbors, were administered by the Federal government. This period, known as Reconstruction, ended slavery, mandated equal treatment under the law, and expanded suffrage with the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Constitutional Amendments. Not all of these aspirations would be immediately realized in Louisiana.

Angry white southerners, frustrated with the Confederate loss and new rights for freed slaves and black Americans, pushed back. In Louisiana, this manifested in lawful (at the time) persecution —including segregation and disenfranchisement through poll taxes and literacy tests — as well as illegal violence — including lynching and voter intimidation — by the Ku Klux Klan, White League and other white-supremacist groups. The state’s 1898 Constitution wrote into law voting restrictions that decimated voting power among blacks and poor whites. In the 1896 presidential election, 101,000 Louisianans cast votes. That number dropped to 68,000 in 1900 and 54,000 in 1904. The voting restrictions made Louisiana, at least politically, a one-party and one-race state.

The 1896 Supreme Court Case, Plessy v. Ferguson, originated in Louisiana and confirmed the constitutionality of segregation. Once black Louisianans lost the right to vote and downstream political representation, they faced underfunded schools, inadequate public services, and unequal legal treatment. This legal racism would continue until the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education and the Civil and Voting Rights Acts later in the 20th Century. As such, Louisiana would see much of its black population leave as a part of The Great Migration, when blacks in the south emigrated north and west for better social and economic opportunities. Whereas in 1900 Louisiana’s population was 47% black, by 1970 it was 30%.

20th Century Politics and Economics

Earlier in the century, as the country was suffering through the Great Depression, Louisiana’s famed governor Huey Long decided to run for president. The governor believed that Roosevelt’s New Deal didn’t go far enough and advocated even more populist and progressive solutions. He had aggressively pursued a similar agenda as the state’s leader — championing infrastructure projects, oil taxes, and wealth distribution. Long was assassinated in 1935 and Louisiana remained safely in the Democratic fold, voting for Roosevelt by margins upwards of 70% in his first three elections and over 60% in 1944.

By the end of World War II, Louisiana had shifted both economically and politically. Defense and industrial jobs had concentrated the state’s populace into its urban regions — the two biggest of which were New Orleans and Baton Rouge. Meanwhile, in 1948, Louisiana broke with the Democratic Party for the first time since 1876. In opposition to the party’s new stance on civil rights, Louisiana voted, along with three other southern states, for the State’s Rights candidate, Strom Thurmond.

For the next 50 years, Louisiana would swing between parties. It voted for Democratic candidates in 1952 (Stevenson), 1960 (Kennedy), 1976 (Carter) 1992 (Clinton), and 1996 (Clinton). Republicans carried Louisiana in 1956 (Eisenhower), 1964 (Goldwater), 1972 (Nixon), 1980 (Reagan), 1984 (Reagan, and 1988 (Bush). In the 1968 election, Louisiana voted for the segregationist American Independent candidate George Wallace. Taken together, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 can be seen as the dividing line for Louisiana. Before that, the state regularly voted Democratic. After the 1964 Civil Rights legislation, Louisiana would only vote Democratic when southerners (Carter and Clinton) led the ticket.

In the later 20th Century, New Orleans was overtaken by other southern cities like Atlanta, Dallas, and Houston. The state’s notoriously corrupt and ineffective government failed to keep New Orleans and Louisiana as successful as its peers as public schools, wages, incarceration rates, income gaps, obesity, and crime all took turns for the worse. The city hemorrhaged its population, which declined from 630,000 in 1960 to 485,000 in 2000. People were leaving for these booming metropolises of the “New South” as well as urban areas in the north and west. People were also migrating from the city to its suburbs.

The population would continue to fall after a series of Hurricanes in the early 2000s, most notably in 2005. That year, Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans — killing over 1,500 people, destroyed homes and city infrastructure, and leaving two million homeless or displaced. The hurricane also hit the state’s economy and about 200,000 Louisianans lost their jobs. Fifteen years later, the state and city have largely recovered from the economic damage of the flood. In January 2020, before the current public health crisis, Louisiana’s unemployment rate was at 5.3%, down from its peak of 15.9% in 2005.

In recent years, Louisiana became known as a cultural center in the South. New Orleans, though still economically reliant on its ports, has shifted towards service and entertainment industries aimed at tourists. Famous for its Jazz music and Mardi Gras celebrations, New Orleans draws nearly 20 million tourists every year. Along with the tourism and entertainment industries, Louisiana’s oil, gas, transportation and agricultural industries reign.

North v. South or Rural v. Urban

Louisiana’s longstanding political and cultural divide used to be north versus south. In the 20th Century, the Catholic southern half would regularly vote Democratic while the Protestant north would vote Republican. There is perhaps no better example of this than the 1960 election — when John Kennedy’s Catholic roots were a major question of the campaign. In the 1960 results, this north-south divide is clear. Almost all of the state’s southern parishes (Louisiana is divided into “parishes” rather than “counties” due to its Napoleonic history) voted for Kennedy while the northern half voted more heavily for Richard Nixon.

The trend is just as vivid in 1964 and successive elections. In the more recent years another trend begins to infiltrate the state’s political divide and eventually come to dominate it: the urban-rural divide. While as recently as 1996, Bill Clinton was able to win large swaths of the rural population, no Democrat would carry rural Louisiana, in particular the ancestrally Democratic Acadiana, since.

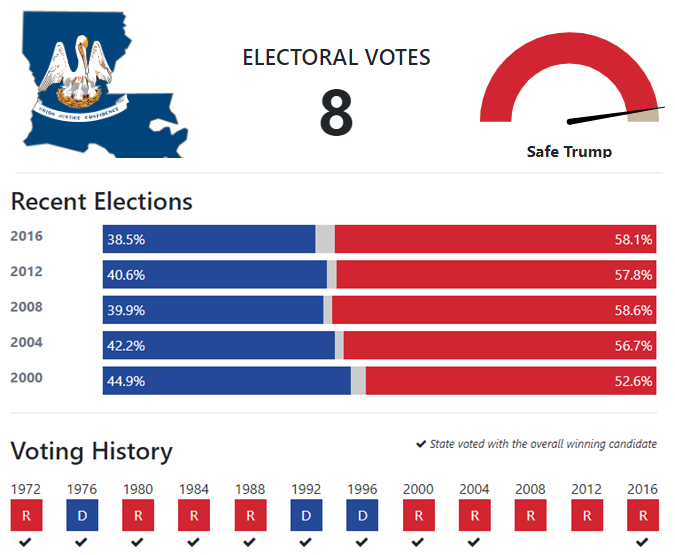

Recent Election Trends; a Democratic Victory

In 2000, the Democratic Party’s leftward shift on cultural issues — the environment, abortion, guns — lost them rural Louisiana, and with it, any real chance of winning the state’s electoral college votes. That year, George W. Bush won Louisiana by 8%, a 20% swing from Bill Clintons 12% victory four years earlier. Since 2000, the state has continued its rightward trend — going to Bush by 15% in 2004, McCain by 19% in 2008, Romney by 17% in 2012 and to Trump by 20% in 2016.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton improved on Barack Obama’s 2012 margin in only six parishes. Three of these (Orleans, East Baton Rouge, and Lafayette) are home to three of the state’s four biggest cities. Two (St. Tammany and Jefferson) are in the New Orleans suburbs. And one (East Carroll is in the Mississippi Delta with a population that is 69% black.

The swing in 2016 is in line with the state’s overall trend going back to 2000. Urban areas becoming ever more Democratic and rural ones more Republican. Suburban parishes, like Jefferson Parish outside New Orleans, may still have gone to Trump in 2016, but Democrats are inching closer. The dual demographic shifts of Hispanic and African-American voters moving into the state’s urban and suburban regions and college-educated white voters turning away from the Republican party has pushed the regions towards Democrats. Meanwhile, Republicans have racked up larger totals in the state’s rural regions, overwhelming Democratic gains and making Louisiana a safe bet in presidential years.

Last year, Democrat John Bel Edwards was able to pull off an unusual victory in the state’s gubernatorial election. Edwards won by increasing the black share of the electorate, increasing margins among college-educated white voters, and holding on to enough rural white voters to not get swamped by them in the final tally. Still, it is far easier to pull voters away from their partisan loyalties in non-federal elections.

J. Miles Coleman of Sabato’s Crystal Ball writes that “the conventional winning formula for a Democrat in Louisiana is 30% of the white vote combined with a 30% black electorate.” Edwards managed to pull off a win using this formula last year, but he was a popular and socially moderate incumbent running in a non-federal election. It’s difficult to imagine any Democrat being able to maneuver the Louisiana electorate so deftly in a presidential election. Given that Joe Biden will almost certainly be unable to thread this needle in the polarized environment of a presidential election, Donald Trump is a safe bet to win Louisiana.

Next Week: Illinois